Maybe better questions are: When is the right time to disagree? And when is it time to align? Wouldn’t it be great if everyone always agreed with you? If you were always right? … Except… how would you know you are?

I think many of us like that there are different viewpoints, that there are people who challenge how we think. It’s just that we don’t necessarily like to be challenged directly and/or unexpectedly. Many of us like different points of view only when we find them convenient, when we look for them, not when someone presents them to us unprompted.

Getting good at disagreement is quite difficult. Disagreements can quickly become unhelpful and unproductive. Often, when people disagree, no one is listening properly, and instead, everyone is stuck in an endless ‘yeah, but…’ loop in their own head. In the end, they part ways with their individual opinions firmed up, and more disconnected from one another.

That, too, feels difficult.

Our brains don’t like disagreement. We are hard-wired for connection and often interpret disagreements as a threat or an attack to social connections. Disagreements can feel like social rejection. Your body and mind want to protect you from that. Our relationships with other humans have kept us safe and protected over thousands of years. When there is a glimmer of threat to that our brain responds, which often leads us to avoid disagreements, conflict, and hard conversations.

Instead of leaning into a conversation about the disagreement, we try to play nice. We might be friendly, but also increasingly vague and non-committal. We stay positive, but we are less and less real, which diminishes any meaningful connection. Disagreements and hard conversations about them can (and should) still build the relationship. (I have written about how the conversation is the relationship in an earlier blog - have a read of that first to familiarise yourself with the idea.)

Whether it is in family dynamics, in friendships, at work or at your local sports club, where there are different people, you will get different views and opinions. But again, we are wired for connection, so we want to be understood by those around us. In order to be understood, we need to be vulnerable, and we need to be able to speak openly while others listen deeply and with care. This requires authenticity and also emotional awareness, and maturity of everyone involved.

It also means that sometimes it’s your job to talk and share your perspective, and sometimes it’s your job to listen. Really listen.

Don’t confuse a disagreement with an argument.

Here are some of the key differences between disagreements and arguments:

The tone of a disagreement is calm and respectful.

The tone of an argument is heated, and the volume might be much louder.

The goal of a disagreement is to understand and resolve.

The goal of an argument is to win or prove a point.

The focus of disagreements is ideas and perspectives.

The focus of arguments is people and personalities.

The communication during a disagreement includes sharing and listening.

The communication during an argument may include interrupting and blaming.

The outcome of a disagreement is collaboration and growth.

The outcome of an argument is division and tension.

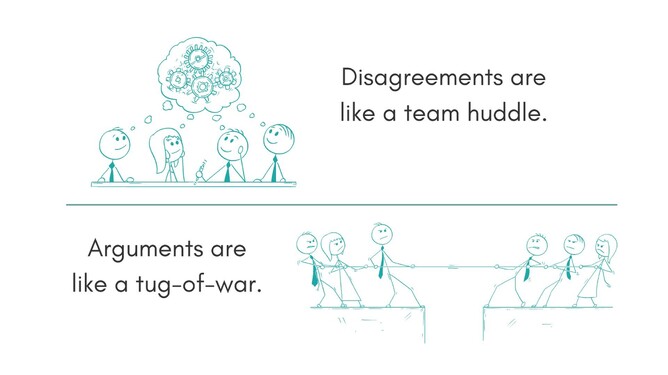

Or, to give you a couple of analogies:

A disagreement is like a team huddle.

An argument is like a tug-of-war.

Disagreements are not about trying to be right or to win; disagreements are about shared problems that need solving. So, ideally, you can put the problem on the table and discuss it safely. This conversation, while it might discuss different views and opinions, should be focused on solving the problem in a way that builds or, at the very least, maintains the same quality relationship that you had with the other people involved.

A disagreement is an invitation to build a bridge. It says, “You don’t (yet) understand my perspective,” and “I don’t (yet) understand yours.” A disagreement is not an invitation for a battle that creates winners and losers, and yet, many disagreements evolve into arguments or lie dormant under a layer of superficial niceties that do nothing to strengthen and build the relationship.

The first people to model disagreements to us are our parents or caregivers. Later, we observe how teachers, coaches, and leaders navigate disagreements: if they tolerate disagreement and can have productive and healthy disagreements, it creates an environment where disagreements are accepted as part of the process of solving shared problems. Everyone learns the behaviours accepted in that environment. If the people we look to don’t model helpful ways of disagreeing, it is likely that they create an environment or a culture that is full of unhelpful disagreement.

People don’t do what you say, they copy what you do. The behaviour around us sets the standard for everything, including how we agree and disagree with each other.

Relationships and environments where helpful disagreements are possible basically say to the individual, “Your challenge is safe here…” and “You can share what you think.” People might not necessarily agree with you, but it is safe to share your view; people will listen and consider it. They will still care for you as a person, even if they disagree with your view.

Be aware that you might be one of the leaders in your environment. Are you a parent? Are you a teacher or a coach? Are you a leader? How do you act and react when you are challenged? How do you act and react when someone disagrees with you?

Just like feedback, conversations about disagreement should still be focused on the issue at hand, not the person. Focus on the issue or task, the problem that needs solving.

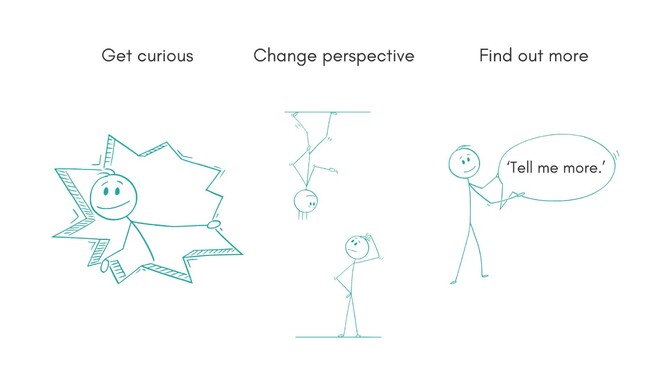

If you find yourself in disagreement with something or someone, remember what the goal is: to understand and resolve. There are a few strategies you can try when you are confronted with disagreement, your own or someone else's:

Get curious. Ask yourself, “What do I not know about this yet?” - with this, you check whether you have any blind spots.

Change perspective. Ask yourself, “Is there a different way of looking at this?”

Find out more. If you are in conversation with someone, prompt them by saying, “Tell me more.” This invites them to give you more details on their point of view and their thinking.

Now, I think one last but important aspect of disagreeing is timing. When is it time to disagree? And when is it time to get aligned?

In my view, there is a time and place for disagreements, and then there is a time and place to get aligned. Not everyone has understood this - (or would agree, I suppose ;)

When to disagree:

Generally, before a final decision is made. During the discussions, before a final decision is made, is the right time and place for disagreements. Any concerns, issues and different perspectives should be raised before the decision point to enable everyone to come to the best possible conclusion. Here are some reasons to voice disagreement:

To protect values. Raise concerns when you think an approach, strategy or particular behaviour is in contradiction with your own, the team’s, or the organisation’s values.

To improve performance. It’s important to suggest a better strategy or point out errors or flaws when you become aware of them to enable an improvement of the overall performance.

To facilitate innovation. Innovation often comes from a place of some tension. Suggest a new idea or approach and allow others to get to know the idea, question and explore it.

To build trust. Honest feedback is important to build trust and demonstrate that you and here to support each other to grow.

To clarify confusion, ask questions when the approach or instructions are unclear.

Here are a couple of examples:

A colleague privately tells another colleague, “In the last team meeting, your tone came across as dismissive to some team members. I don't believe you intended this, but I thought I should let you know.” This opens up a constructive conversation and builds mutual respect.

During a conversation about screen time rules, one parent says, “I’m worried this isn’t consistent with what we agreed last week.”

“This approach feels off-brand — can we revisit how it aligns with our values?”

“Sorry, I didn’t quite follow that part — could you clarify?”

Most people appreciate it if you disagree early and privately or in smaller group conversations rather than in a big, open, and public forum.

It may sound simple, but disagreeing isn’t necessarily easy. It might take some courage to address behaviour or raise something you are opposed to.

When to be aligned:

Generally, after a decision has been made, when it is about to be communicated to anyone affected by the decision. If a decision has been made, it is important that all team members stand behind the decision, regardless of any initial disagreement. The same is often true for parents, coaches, teachers, and anyone else in charge of or caring for other people. Here are some reasons why it is helpful to maintain alignment after the decision has been made:

To maintain trust. Disagreeing behind people’s backs after decisions have been made undermines trust, not only of the people whose backs you are talking behind, but also everyone else who witnesses you disagreeing with the decision you were part of making. You are showing them that you would undermine them, too, if you disagreed with a decision they made.

To model the unity you want to see from others. If you want your team to act like a team and present a united front, you need to model this as a leadership team, coaching team, etc.

To focus on the execution of the decision, rather than a re-discussion. Usually, the job isn’t done once the decision has been made. The decision still needs to be implemented and reinforced. This is not the time to re-discuss.

Here are a few examples:

A leadership team debates internally whether to delay a product launch. Once they decide to delay, they all commit to presenting the decision confidently to the company. No one later says, “I wasn’t on board,” even if they had concerns earlier.

School staff have differing views on how to handle mobile phone use in classrooms. After discussing and agreeing on a policy, they present it together to staff, students and parents with a united front, demonstrating consistency in leadership.

A sports coaching team debates player selection for an upcoming match. After agreeing on the lineup, all coaches backed the decision, focusing on helping the team succeed rather than second-guessing the choice during training or in front of players.

The key here, as so often, is that you communicate clearly, early, and often. No point going through a whole decision-making process with leaders or as coaches if you haven’t connected with the people who will be affected by the decision(s) and found out what they want, what they might worry about, and what their priorities might be.

That’s all for this week. Thank you for taking the time to read it all. If you found this useful or you know someone else who might, please share it.

Key Points:

Disagreements and arguments are two different things. Make sure you know which one you are currently engaged in.

There is a time and a place to disagree and a time and a place to align.

Clear and consistent communication throughout makes it easier for people to understand your perspective(s), process(es), and decision(s).

Reflective questions:

How safe are the environments you operate in to disagree?

In what ways are you yourself making it safe (or unsafe) for others to disagree?

How could you practise healthy disagreement?

When did you miss an opportunity to disagree?

When did you continue to disagree long after it was time to get aligned?