Strategies to regulate emotions

Our lives are full of emotion. We might be excited about an upcoming trip, sad that we had to say goodbye to friends we won’t see for a few months, and we get nervous when we have to give a presentation or are up for a job interview. And then there are moments of envy as you compare yourself to others, be it friends or strangers online, moments of frustration when someone cuts in line, moments of desperation when you feel like your partner isn’t listening to you and moments of gratitude for life and all you have while watching a sunset. A beautiful up and down of feelings…

As I’ve explained in the last blog: we all have emotions. It’s quite useful really, because emotions mainly do three things for us:

They prepare us for action.

They help us communicate.

They give us a deeper experience of life.

We also can’t stop our emotions; you don’t want to stop them either. They are information worth paying attention to because they alert us to our needs. The need sits underneath the emotion and until we address that need, the emotion isn’t going away. If you’d like to learn more about emotions and why we have them, please read that blog post first. (Please note, we can temporarily delay processing emotions, suppress them, etc. but that is a blog for a different day.)

Today, I’ll share strategies that help you build emotional awareness and emotion regulation skills. While emotions give us a deeper experience of life, the highs and the lows, experiencing lots of emotions at once or in quick succession can feel intense and exhausting. Emotions themselves are not harmful. They are neither good nor bad; they are just part of being human. What matters is how we engage with them, interpret them, and how we choose to respond.

You might have noticed that there are days when nothing phases you. And then there are other days when you feel furious about everything. So, some days, your emotional responses are proportionate to the events that prompt the emotion. On other days, it might be disproportionate. For example, you might get stuck in traffic and someone pulls into your lane unexpectedly. A proportionate emotional response might be feeling a little annoyed, you might roll your eyes, and you might sigh.

Now imagine yourself in the same situation. But this time, you get stuck in traffic after you've spilt coffee down the front of your shirt and then hastily got changed before leaving for work. Now, you are in a rush. When you got in the car, your heart rate and muscle tension were already higher because of an adrenaline release earlier that morning. You are already in this elevated state of emotional response, and now your tolerance is much lower. So when the other car pulls into your lane, instead of being annoyed, rolling your eyes and sighing, you feel angry, yell mildly abusive words and then honk your horn at them, because who do they think they are?! That would be a disproportionate response.

Different circumstances might lead to disproportionate responses. Drugs and alcohol, for example, don’t help and might lead to over or under-reactions. Past experiences, physical discomfort, such as pain and hunger, and a lack of sleep also impact.

If you have ever been hangry - you know exactly what I am talking about.

I shared last time that we rowed across Cook Strait, the body of water between New Zealand’s North and South Islands. At one point, we had dolphins swim alongside our boat and honestly, when you spend months planning a challenge like this, having dolphins escort you across is quite special. So we were excited. Despite the pain and exhaustion, we looked around, chatted, and celebrated that this was happening. A proportionate response to dolphins…

Over the next few hours, this happened another couple of times and by the third time, honestly, I really didn’t care about the dolphins… I didn’t look around to see them, I didn’t chat to my teammates and I didn’t feel any of the excitement I had felt the first time around. And I remember thinking, ‘If you don’t care about the dolphins, something is wrong. You need to eat something.’ - sure enough, a few bites out of my cheese sandwich and things looked much better.

Note that this was essentially the same event. The dolphins were the same, but my situation had changed because of the physical discomfort I was in: pain, hunger, tiredness. Compared to my normal or proportionate response, I under-respond; I became withdrawn.

There is an acronym that’s used in relapse prevention and can be used in this context too. To remember what sort of things might make your experience of emotions more intense - think HALT. Ask yourself: Am I Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired? If you are any of those things, you might have a disproportionate response to the situation. The more often you do this, the better and quicker you’ll get at recognising your underlying needs. So this is useful to practise...

Now, there is one other challenge. The area of our brain that generates emotions is different to the one that allows us to regulate our emotions. One is developed earlier than the other. While we can feel the full spectrum of emotions by the end of adolescence, the prefrontal cortex which helps us regulate our emotions, is not fully developed until we are anywhere between 25-32 years old. This means adolescents experience emotions at the same intensity as adults but are less able to regulate them. In addition, they also have less experience to help them understand what is happening and less practice in regulating emotions.

Thankfully we can help. Parents help their children regulate their emotions. You know this if you have ever comforted a child, or tried to make them laugh. Teachers, coaches, friends and colleagues can help us regulate our emotions during adolescence and well into adulthood.

Emotion regulation is a social skill, which means you can help.

(Regulating the emotions of others is not your responsibility, with the possible exception of any children in your care. Kids do need help regulating their emotions and they learn how to do it from their primary caregivers and others around them, e.g., family, teachers, coaches, etc. However, as friends, siblings, relatives, colleagues, ...well, humans, we often support others with empathy, contributing to their emotion regulation and our own.)

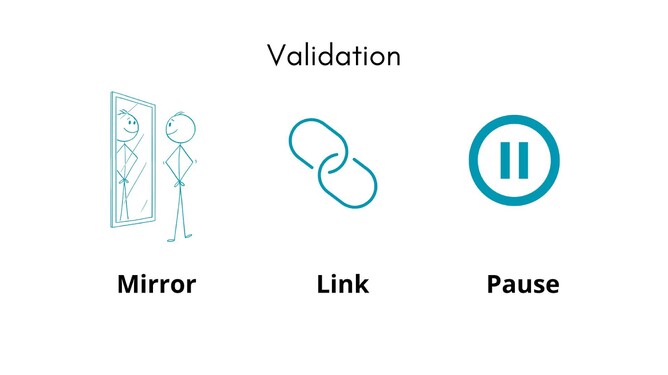

One of the strategies you can use to help others regulate their emotions is validation. If you have ever felt really seen and heard, chances are that someone validated your experience. It helps people move through the emotion more quickly. Emotional validation, in a nutshell, is when you let someone (or yourself) know that their emotions or feelings are heard and understood. Research suggests that validating someone when they are upset quickly reduces their emotional distress. We can also learn to validate ourselves, and similarly, this can reduce our distress in the moment.

The first step of validation is being present. That means you listen, pay attention, and aren’t distracted by your phone. So start validation by being present with others and with yourself. The great thing about validation is that you can do it even if you disagree with the other person’s opinion or perspective. Their emotional experience is real and relevant to them and you can validate that experience.

Say, when supporting a friend, you can say, ‘I can understand that you are frustrated, that makes sense, you worked so hard recently and the delay of your trip is upsetting.’

Note that you aren't offering a solution. Instead, there is a simple pattern. Try to name the emotion: ‘I understand that you are frustrated.’ - Dan Siegel calls this ‘Name it to tame it’ - name the emotion. Mirror it. Reflect it back to them. They might be excited, angry, or scared. Sometimes it is hard to figure out what exactly the emotion is, so you can say, ‘I’m not sure what you are feeling, you seem upset.’

Then, link this to what seems to have prompted the emotional experience. ‘You’ve worked hard recently and the delay of your trip is upsetting’. So name or mirror the emotion, then link it to whatever prompted it, if you can.

And then, and this is THE most important step of validation:

PAUSE.

Don’t say anything.

This is also the hardest part because we want to help and offer a solution. The thing is, the other person doesn’t need a solution, yet (and they might not ever need one from us). They need to feel seen and heard.

As soon as you offer a solution, you undo the validation you have just put in place. So pause. It allows the person to connect with themselves to figure out what they need. Remember, the emotion is like a notification for a need that sits underneath it. And remember, you can validate your own emotions. We often forget that we can. But it works just as well.

So, to validate, think:

Mirror – Reflect back (or mirror) what you observe the other person feeling (e.g. You seem upset/angry/sad...)

Link - Link this emotion to the person’s situation and/or to what has prompted the emotion. (e.g. 'Your frustration makes sense – this is hard.')

Pause – allow time for the person to hear that you’ve noticed their distress. Important: DO NOT offer a solution. This is not the time for solutions yet. Give the person space. If you feel the need to say something, ask a question. E.g. “How can I help? or What do you need?”

We can regulate emotions at different levels. As you read through them, you might recognise that you do this regularly already:

At the situation level, we can regulate emotion by choosing which situations we are exposing ourselves to. Say, if you (like me) are a little scared of dogs, you might ask your friend to leave their dog at home when they meet you and you might not run through a dog park on your morning jog.

At the attention level, we can regulate emotions by managing how and what we pay attention to, for example, you might turn away from the injection when having a blood test.

At the appraisal level, we can regulate our emotions by changing our thoughts about the experience, for example, if the interpretation of an event is ambiguous, you can choose to appraise it in a more positive light, e.g. when a friend does not wave at you, you can choose to think they didn’t see you, rather than that they deliberately did not want to engage with you.

At the response level, emotion regulation would involve making decisions about how we choose to respond and behave, for example, you might feel yourself getting angry, and choose to resist the urge to respond in anger, by walking away to calm down.

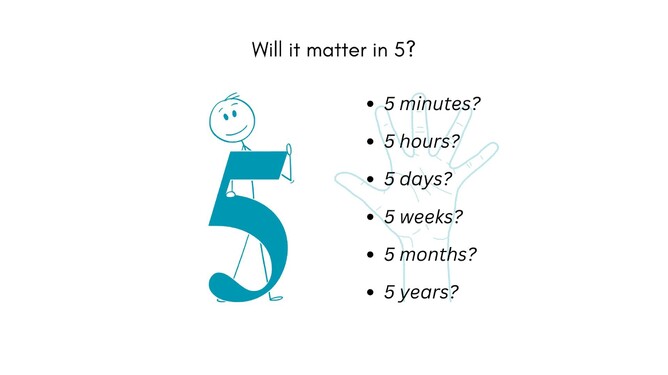

An example of a strategy that helps you reappraise a situation is ‘Will it matter in 5?’ This is a strategy that encourages you to shift your time perspective. In situations where you find yourself getting worked up, upset, angry, or frustrated, ask yourself:

Will it matter in 5? Will it still bother me in 5?

5 minutes?

5 hours?

5 days?

5 weeks?

5 months?

5 years?

It might initially feel like whatever is happening is important and has a huge impact. However, once you shift your perspective by asking these questions, you create some distance (in this case a different time frame). It’s a good way of gaining perspective, it allows you to decide how important this issue is and how much energy and emotion you want to spend on it right now.

Building awareness using HALT and regulation strategies like validation and 'Will it matter in 5?' takes practice. They are really effective though. And no one has to know that you are practising. :)

Try it.

I hope this blog has been useful and it’s made you think. If you know someone who might find this one helpful, please share it with them. As always, I’d love to hear from you. Message me on Instagram @mankertina

Key Points:

Depending on circumstances and how we are feeling in the moment, we might react differently to the same event. We might over- or under-respond; or have a proportionate or disproportionate reaction to something.

Emotion regulation is a skill set we can learn and practise.

Emotion regulation is a social skill. We learn it from each other and can help each other regulate our emotions.

Reflection Questions:

When have you had a proportionate response to something? When have you had a disproportionate response, i.e. when have you either over or under-responded to something? And why? (were you hungry, tired, already frustrated with the situation or person, etc.?)

How do you regulate your emotions at different levels? Reflect on last week: What examples of emotion regulation can you recall for situation, attention, appraisal, and response levels?

When and how have you helped others regulate their emotions? Through listening, validation, helping them shift their perspective, etc.?

Which one of the strategies I have introduced will you try this week?

If you are interested in further reading about different emotions, here are a couple of books I have found useful and easy to read:

Brown, Brené, Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. New York, Random House, 2021.

Rebekah Lipp, Illustrator: Craig Phillips, Title: "How Do I Feel? A Dictionary of Emotions for Children", Publisher: Wildling Books

Pastiroff, S. (2020). The Mindful Parent: How to Stay Sane, Stay Calm and Stay Connected to Your Kids. Renew your mind publishing.

If you are after the research, look here:

Gross, J. J. (Ed.). (2007). Handbook of emotion regulation. The Guilford Press. Lochner.

Mills KL, Goddings AL, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore SJ. The developmental mismatch in structural brain maturation during adolescence. Dev Neurosci. 2014;36(3-4):147-60. doi: 10.1159/000362328. Epub 2014 Jun 27. PMID: 24993606.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74(1), 224.